History

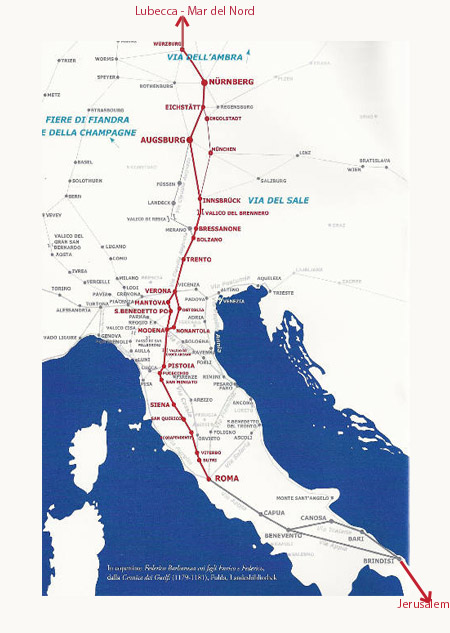

The connection between the Latin-Mediterranean and Germanic worlds became important with the Roman Empire and continued throughout the Middle Ages for economic, religious and political reasons. In particular, this road played a prominent role until 1266, when the Angevins, French, defeated Conradin, the last heir of the great Frederick II of Swabia.

The privileged relationship between Germany and Italy that developed on these roads then experienced a setback, which lasted for several centuries, in favor of connections with France.

Entire peoples passed along the north-south axis: Gauls, Celts and Etruscans, the Romans and the hordes of barbarians who put an end to the Roman Empire. It was at the center of the events of the municipalities and the seigniories, the Renaissance that was born in Tuscany, the battles of the Risorgimento in the Po Valley, the two world wars.

Tra i personaggi storici ricordiamo San Francesco che da Assisi arrivò a Firenze passando nel Valdarno, e Martin Lutero lungo l’Adige; Matilde di Canossa, quasi la “madrina” della nostra VIA, di cui incontriamo tracce dal Valdarno al mantovano e a San Benedetto Po, ove chiese di essere sepolta nella abbazia fondata dal nonno. Vi passarono diversi Papi e Imperatori, oltre sessanta, tra cui Enrico IV umiliato a Canossa e il Barbarossa.

Among the historical figures we remember St. Francis who arrived in Florence from Assisi passing through the Valdarno, and Martin Luther along the Adige; Matilda of Canossa, almost the “godmother” of our VIA, of which we find traces from Valdarno to Mantua and to San Benedetto Po, where she asked to be buried in the abbey founded by her grandfather. Several Popes and Emperors passed through it, more than sixty, including Henry IV humiliated at Canossa and Barbarossa.

The Imperiale proposes many ancient roads: Roman Consular roads, Renaissance and eighteenth-century roads; but also land and water trade routes (between Modena, the Po and Mantua) and devotional routes (San Bartolomeo).

And finally the Habsburg Via Regia, still today one of the most important arteries leading to central-northern Europe, which was commissioned by Leopold of Lorraine and Francesco d’Este to connect Florence to Vienna, capital of the Habsburg Empire to which both families were linked by dynastic descent. This road was the first European highway and was traveled by many artists for their Grand Tours which, from the nineteenth century, created the image of Italy as a tourist and cultural destination.

Below are the cards that briefly illustrate the different segments that make up the Via Imperiale.

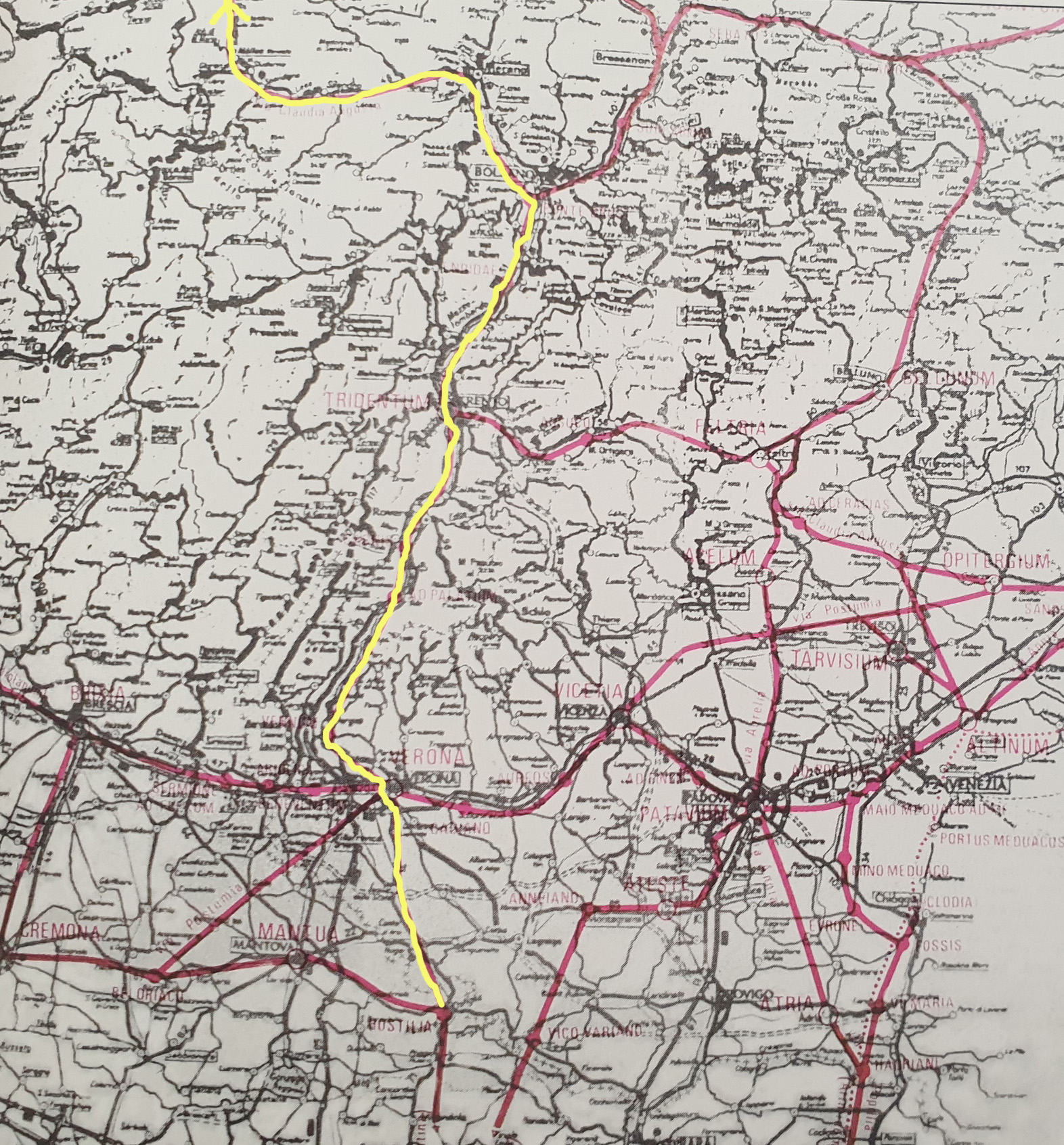

Via Claudia Augusta – from Trento to Verona

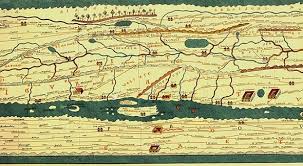

La Via Claudia Augusta fu costruita in onore di Ottaviano Augusto a partire dal 12 d.c. Aveva due bracci, che collegavano l’Adriatico e il Po. Noi ripercorriamo con la Via Romea Imperiale il braccio detto “Padano” nato come via militare (la sua variante Altinate, diretta al mare, aveva invece scopi prevalentemente commerciali). Importantissima durante l’impero, alla sua caduta cominciò a perdersi in decine di sentieri, mulattiere e strade cosparse di storia e leggende.

L’obiettivo della strada era la velocità, per unire nel più breve tempo possibile punti tra loro geograficamente e culturalmente lontanissimi: il porto di Altino sull’Adriatico (770 km circa) e quello di Ostiglia sul Po (641 km circa) con il confine settentrionale dell’impero, Donauwörth, sul Danubio, a nord di Augusta, transitando per la valle dell’Adige, la Val Venosta, parte della valle dell’Inn, il Fernerpass, la Lechtal e quindi le distese della pianura bavarese. Lì c’era il limes e iniziava il mondo dei “barbari” con gli spettri dei legionari massacrati per mano delle tribù germaniche nella battaglia della foresta di Teutoburgo (Bassa Sassonia, 9 d.C.).

La Via Claudia Augusta ripercorre la rotta nord-sud, che dalla caduta dell’impero romano a tutto l’alto medioevo ha visto transitare innumerevoli popolazioni, attirate dal sole e dal calore mediterraneo, vagheggiando una terra prolifica e fertile. Questa via fu ripercorsa in seguito da artisti, intellettuali e ambasciatori che, nei secoli, scendevano nei grand tour paesi italiani per entrare in contatto con l’ormai perduta ma sempre agognata classicità. Oggi percorrere la Via Claudia Augusta vuol dire dare un forte senso di unità, tra culture diverse, in piena sintonia con lo spirito romano del tempo. Infatti, per quel popolo che aveva colonizzato buona parte del mondo allora noto, conquistare le terre significava rimescolare gli uomini, facendo di Roma una terra di asilo di uomini, di dèi, di usi e costumi: la cultura romana si basava appunto non sulla chiusura ma sull’apertura al mondo, lezione mai imparata abbastanza dai paesi europei.

Costruire la Via Claudia Augusta, la strada della Rezia, non fu impresa facile. Soltanto dopo aver scavalcato il Fernpass (Tirolo) e le imponenti montagne alpine, la strada scivola dolcemente nella valle del fiume Lech, entrando poi nell’ondulata pianura bavarese (l’antica Svevia). La strada terminava in corrispondenza della città romana di Augusta. Da Augusta Vindelicum la Via venne prolungata successivamente di una quarantina di chilometri a nord, raggiungendo Donauwörth, l’antica Werd, affacciata sul Danubio: il fiume rappresentava il Werd, il confine, il limes.

La Via Claudia Augusta aveva anche una funzione ideologica e simbolica: nella formula a flumine Pado ad flumen Danuvium risiede l’idea di superamento della barriera alpina e di collegamento fra due mondi racchiusi tra il principale fiume d’Italia e il maggior fiume conosciuto dai Romani al di là delle Alpi, il Danubio.

Nella costruzione di questa e di tutte le loro strade, i Romani si preoccupavano di rispettare una regola ben precisa: la strada doveva essere veloce, sicura, solida, di facile manutenzione, con ottima visuale sul territorio e possibilità di difesa rapida. Una regola è la ricerca ossessiva della linea retta, che su terreno mosso significa indifferenza ai saliscendi. La logica del rettilineo ha senso strategico e commerciale, è fatta per sorvolare e attraversare in fretta, non per conoscere.

La Via Claudia Augusta ha la stessa logica delle ferrovie militari asburgiche costruite tra l’Ottocento e il Novecento in Tirolo: transitavano lontane dai centri abitati e seguivano una linea il più possibile retta. A costruire la Claudia Augusta furono i soldati della legione di Druso: metro dopo metro, inghiaiandola o battendo il fondo naturale, lavorando dalle 8 del 10 mattino alle 15 del pomeriggio. Soltanto nei pressi e negli attraversamenti dei centri abitati più importanti la strada veniva lastricata con pietroni rettangolari. Da questa arteria principale si diramava un’infinità di bretelle, chiamate vicinales, che collegavano tra loro i villaggi (vici) e le fattorie sparse (rusticae). Il perfetto funzionamento della strada militare era in carico allo stato, mentre per le varianti la cura spettava ai singoli, le municipia locali. A distanze fisse si innalzavano castella, piccoli fortilizi, e stationes o mansiones, punti di sosta e di ristoro, solitamente distanti una trentina di chilometri l’uno dall’altro. Le mansiones erano statali (o almeno le gestivano uomini delegati dallo Stato) e vi si potevano fermare soltanto gli appartenenti all’amministrazione romana. Gli altri dovevano accontentarsi delle mutationes, dove chiunque poteva fermarsi, cambiare i cavalli, i buoi o i muli, trovare di che riparare eventuali guasti, dormire e mangiare. Queste aree di sosta distavano tra le dodici e le diciotto miglia l’una dall’altra. I posti tappa romani sono gli antenati degli ospitali medioevali (e degli odierni motels sulle autostrade). Su quello che rimaneva della Via Claudia Augusta sorsero, a partire dal 1400, associazioni e compagnie che gestivano particolari forme di servizio e di assistenza per viaggiatori diretti in Italia. Tra queste associazioni va ricordata principalmente la Venediger Boten che, proprio da Augusta, organizzava, soprattutto per pellegrini diretti in Oriente, viaggi con destinazione Venezia.

L’unità di misura della strada romana era il milia passuum: mille passi equivalevano al miglio romano e il passuum corrispondente a 1,48 metri; quindi un miglio corrispondeva a 1480 metri. La Via si misurava partendo da Roma o, nel caso della Claudia Augusta, dai due porti di partenza, Altinum e Hostilia. Ad ogni miglio c’era un cippo di pietra su cui era incisa la distanza in miglia e, qualche volta, anche la dedica di chi aveva voluto, o riadattato, la strada. Delle migliaia di miliari collocati sulla Via Claudia Augusta ne sono arrivati noi a noi soltanto quattro.

Sulla strada si trovavano le famigerate locande, ricettacoli della vita, dove ci si poteva imbattere in una variegata società: mercanti sull’orlo della bancarotta, ladri, prostitute, battellieri, carradori, soldati di ventura. Non c’era molta differenza tra una locanda romana e una delle tante taverne così ben descritte dai viaggiatori medievali e riportate nella letteratura del tempo. Però, come ci ricorda il Aristofane le strade senza locande sono peggio di una vita senza vacanze.

Sulle strade romane si viaggiava lentamente: i carri commerciali non superavano le otto/dieci miglia al giorno. Cinquanta miglia era invece la media per i corrieri di stato, i quali cambiavano cavalli ad ogni posto tappa.

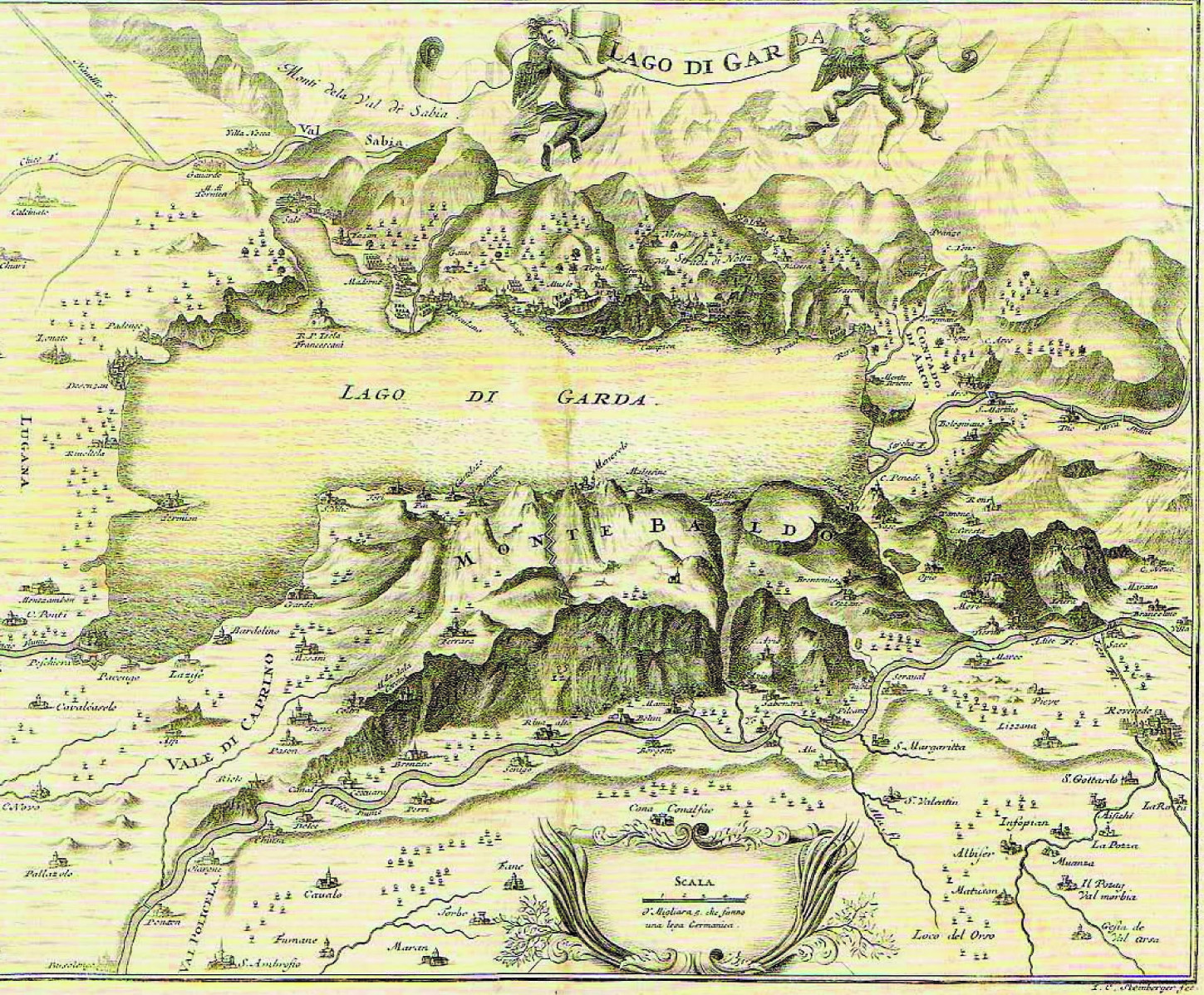

Via Postumia – from Verona to Peschiera and Mantua

This is an important Roman consular road, which owes its name to its builder, Postumius Albinus. Like all consular roads, it was built for the rapid movement of soldiers. Indeed, it cut horizontally through Cisalpine Gaul and connected the most important military garrisons, from Turin to Aquileia.

The itinerary has come down to us thanks to a source from the 4th century A.D. when a pilgrim in the years 333-334 travelled the Itinerarium Burdigalense, from Burdigala – today’s Bordeaux – to Jerusalem and then along the Postumia from west to east. Following his trail, during the Middle Ages, pilgrims and crusaders arrived from France, travelled along Postumia as far as Aquileia, descended to the Balkan peninsula, reached Constantinople and headed for Jerusalem. It thus became a very beaten track, especially in an east-west direction, as it was a key part of the route leading from Eastern Europe to Santiago de Compostela, which had become a very important religious destination. The pilgrims would enter the route at Aquileia and, after walking the entire route, continue on to France.

Today’s Postumia route does not overlap perfectly with the ancient Roman consular road: it deviates from it in favour of safe paths, comfortable dirt tracks and pleasant landscapes. Today’s route links Aquileia to Genoa, crossing six regions of northern Italy, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, Veneto, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna, Piedmont and then bends towards Liguria. It crosses the Apennines in the province of Alessandria and descends to Genoa.

This route meets the Via Romea Imperiale in a very fascinating stretch, from Verona to Mantua, with two itineraries through picturesque fortified villages, also touching on Lake Garda. Postumia and Imperiale combine to create a network of paths available to slow tourism, in the footsteps of the many pilgrims who then continue their journey, southwards to Rome or westwards to Santiago de Compostela.

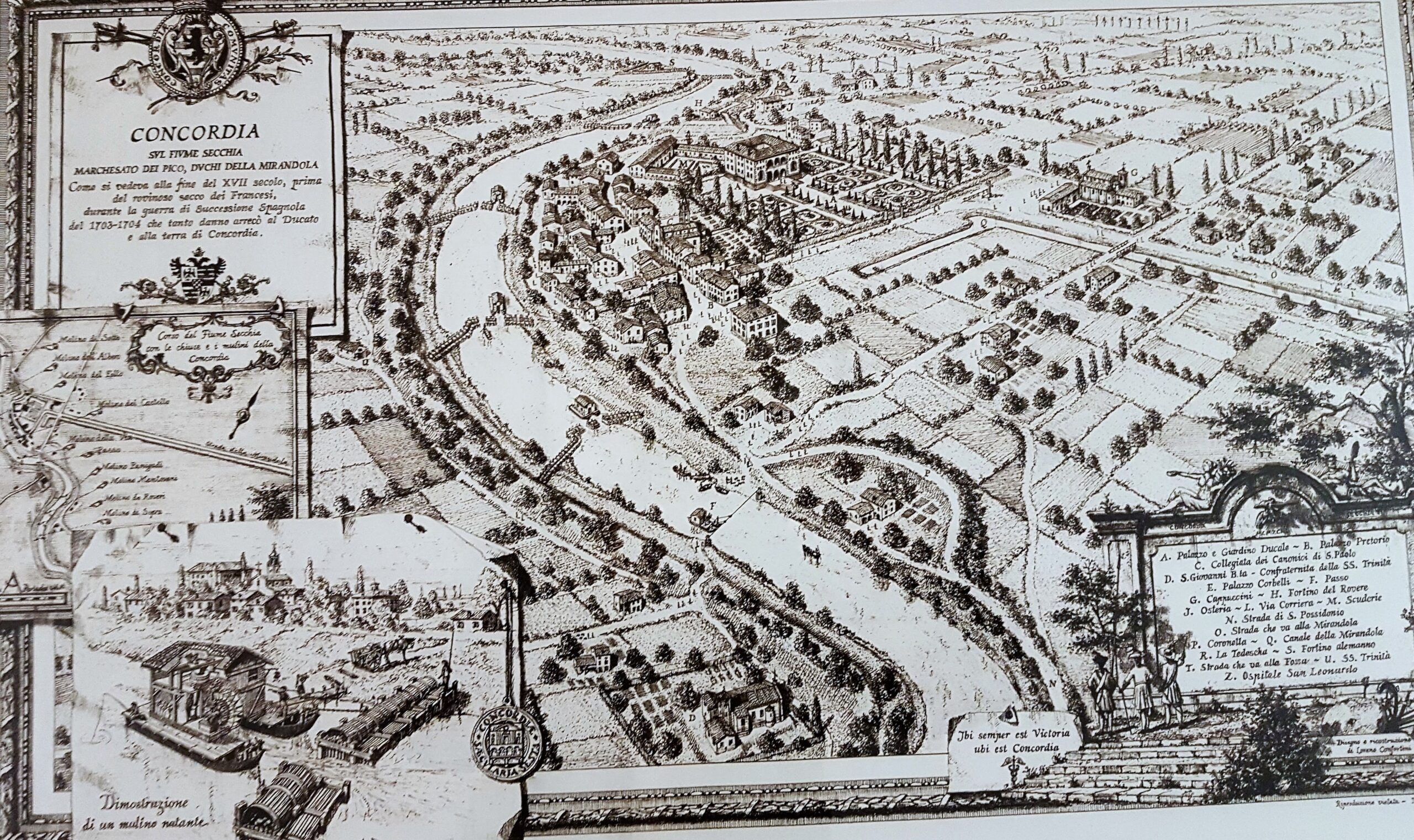

Watercourses from Peschiera to Modena

The presence of watercourses has always characterised the territories along their banks, favouring the transit of goods and people, representing strategic points where new settlements could be founded to control traffic and trade.

From Pavia to the delta, the course of the Po was for centuries the main communication route in northern Italy, until the advent of the railway.

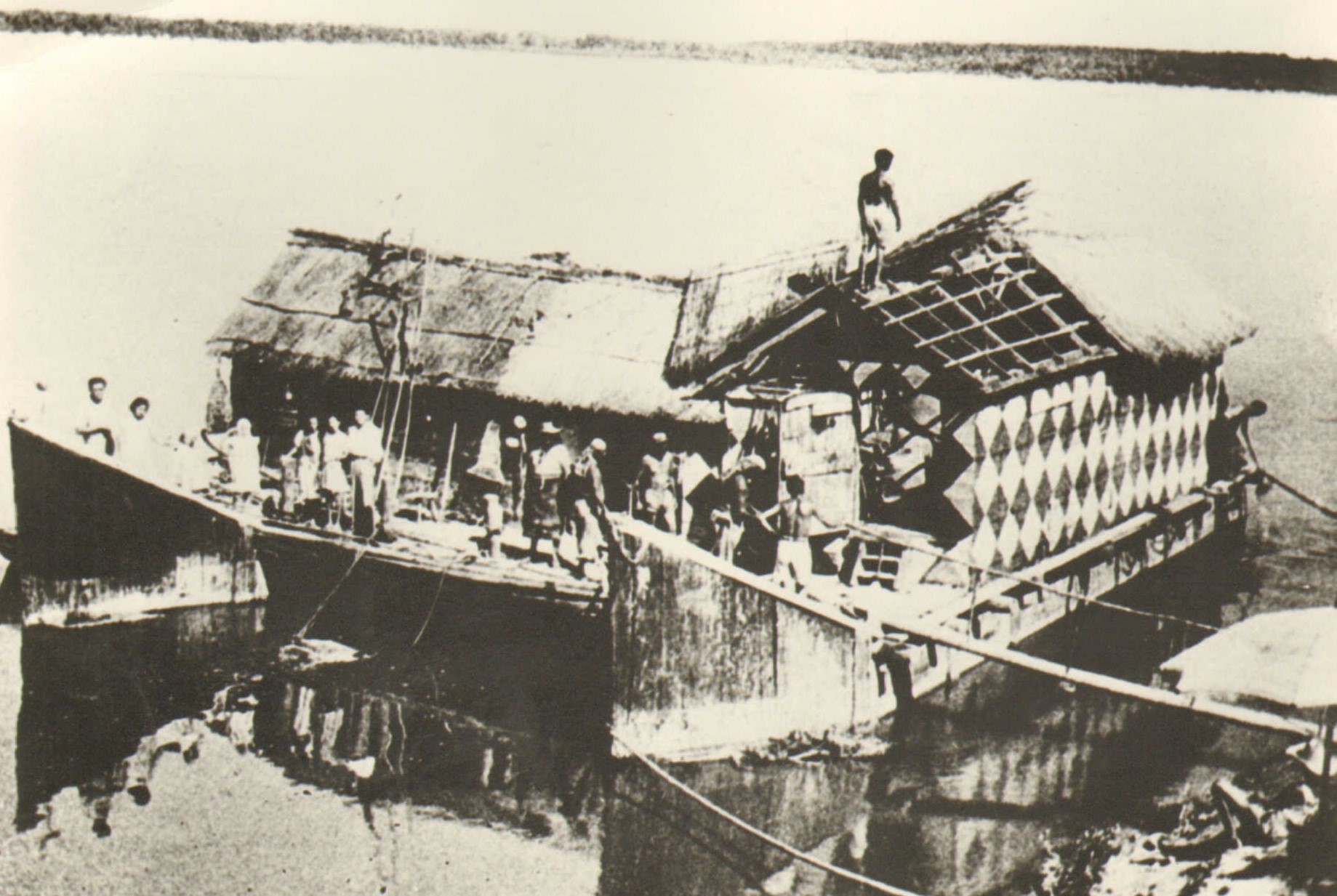

In the early Middle Ages, river traffic was largely managed by ecclesiastical bodies and monasteries, which used their own ships and people employed by them. With the expansion of trade, a veritable class of navaroli was established, organised in associations.

River navigation has played a very important role since ancient times. On the old transport barges, now only visible in models, they carried gravel, sand, coal, wood, bran, beet, wheat, sugar. Taking advantage of the current, they headed out to the sea; they would sail upstream using sails and oars, or they would tow horses, horse-drawn carts and riders along the banks.

The decline of shipping began with the Austrian occupation, as it was limited to certain boundaries and vessels. Nevertheless there was the introduction, in the first half of the 19th century, of steam navigation.

However, these were isolated initiatives, without continuity, so much so that they disappeared altogether in the second half of the century with the advent of the railway. The resumption of river navigation took place at the beginning of the 20th century, by means of steam tugs.

Along the banks of the Po Valley rivers, it was common to see the silhouette of floating mills, a typical expression of this particular landscape, as well as a source of energy and survival for the riparian populations.

The landscape around the river was also very different from that of today. Along the sandy banks ran the tracks of the horses and oxen that pulled the barges, a space that had to be kept free of any impediment, be it root, tree trunk or bush. In addition to the animal tracks, the actual river woodland began to grow spontaneously. On the banks, the tree vegetation was varied and substantial: there were willows, mulberry trees, alders, cherry trees, locust trees, oaks, which were periodically felled. In the forest there was the possibility of collecting the branches of young willows and acacias to make wicker suitable for baskets and baskets. The forest also offered much shrubbery suitable for weaving to make small household items.

Among the river trades, it is important to mention that of the fisherman, who required great knowledge of the river, which, unlike the sea or the lake, constantly changes in width and depth. His work also took place in winter and at night (except on a full moon).

The river continues to be a source of inspiration for artists, poets and writers, and its banks are the ideal place to observe the surrounding area, which is characterised by sandy islands, poplar groves, farmhouses and a multitude of parish churches, chapels and small villages. A landscape that never ceases to amaze walkers and cyclists, whatever the season.

Taken from the travel guide, edition 2023, Via Romea Imperiale. Federica Guidetti Curator Polironiano Civic Museum of San Benedetto Po (MN).

Crossing the Apennines – from Pavullo to Pistoia

Anyone coming down from the Brenner Pass and heading towards Rome has to cross the Apennines after reaching the Po-Emilia plain. This was the problem of our ancestors, the Etruscans and Romans.

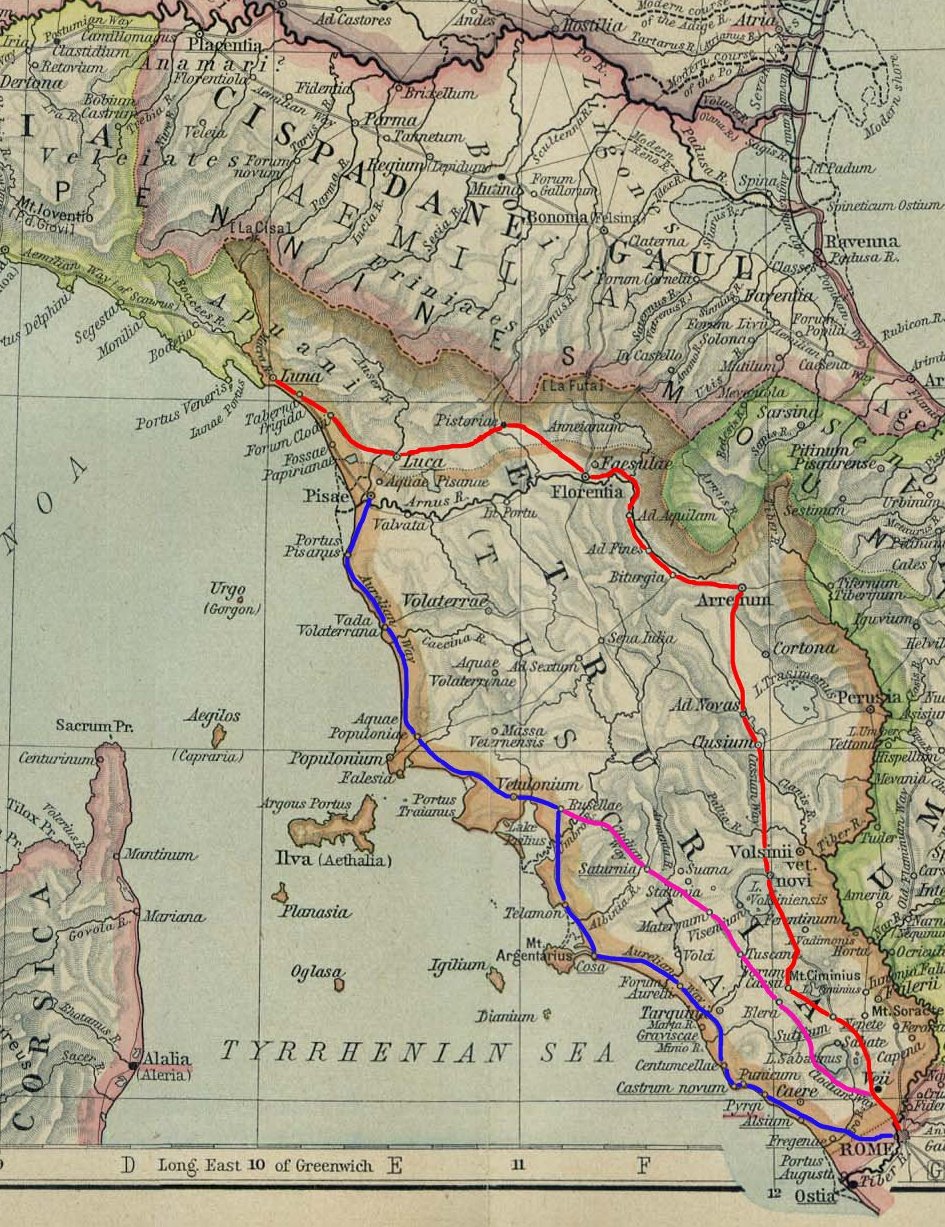

To the north and south of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines ran two Roman consular roads, the Via Emilia and the Via Cassia: the first, starting from the important colony of Rimini, crossed the whole of the Po plain and allowed its progressive “Romanisation”; the second started from Rome and crossed Etruria. In order to connect the two great arteries, roads (such as the Mutina – Pistoria) were built in the first century BC, often called Cassiola or Little Cassia.

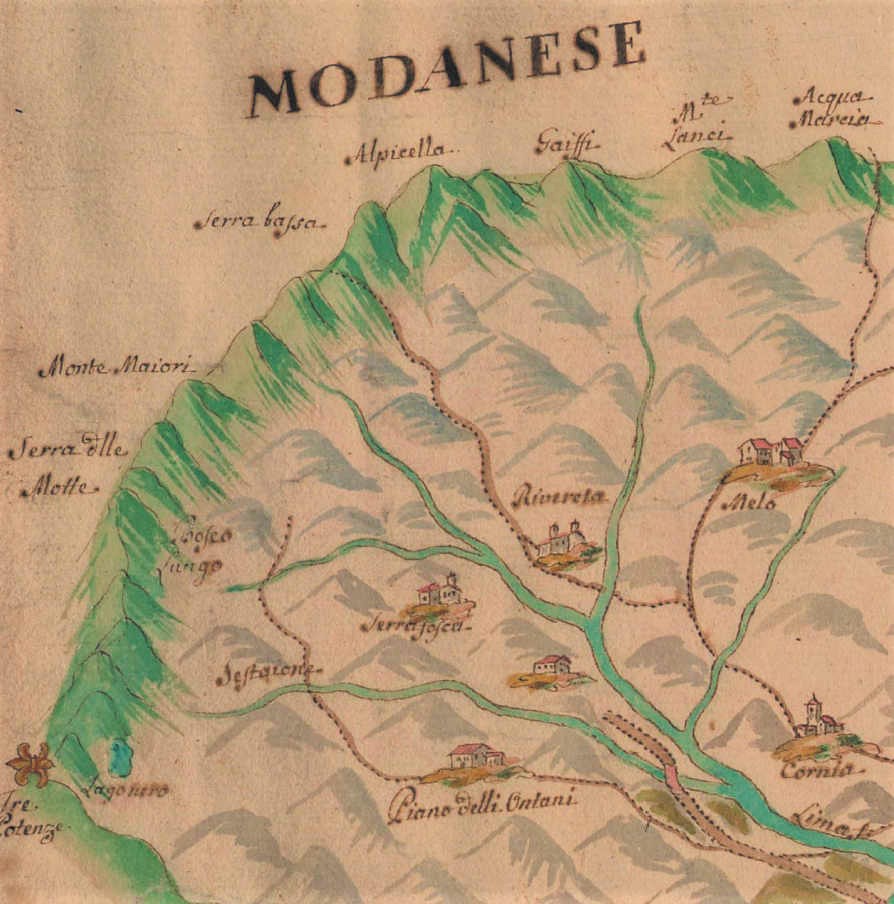

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the roads remained uncertain and unsafe for centuries, narrow mule tracks, impassable in winter and winding to avoid the frequent torrents. The description of the roads in the Modena Apennines in the documents of the time is very significant: “narrow and rough”, “jerky and bad”. “bad, overflowing, steep”. Lodovico Ariosto calls them “via alpestre”, so bumpy that they tore his poor horse.

An important road, perhaps already traced by the Romans and still known in the 16th century as the ‘Romea’ or ‘Strada Ducale’, it ran from Modena to Pistoia and, after reaching the Pavullo plateau, it branched off in various directions towards Tuscany. Alongside the best-known and most popular one that crossed the Leo Valley in the direction of the Calanca Pass, there was also an equally important network of roads that led to Tuscany along the valley of the Scoltenna, the scene of battles between the Romans and the Celts, and later between the Longobards and the Byzantines.

An important turning point in the road system came in the 18th century with the Este family, who wanted to connect Modena to the Tyrrhenian Sea without having to go through the foreign territory of Lucca. The work was entrusted to the mathematician Domenico Vandelli, who completed the project in 1739. It was an innovative project that favoured high altitudes and the almost total abandonment of inhabited areas. Vandelli’s choices were motivated by the desire to find a short route to San Pellegrino, a necessary step to cross the Apennines, since the Radici road was in the territory of Lucca. From 1760, the Via Vandelli began to decline and today it is only used by hikers, who can enjoy the panoramic views of the Tuscan-Emilian Apennines.

On the Tuscan side, in the territory of Pistoia, until the second half of the 18th century, there were only a few impassable paths to cross the fir-covered mountains to the west, climbing up to the Fariola Pass or the Hannibal Pass at 1798 metres, a place name that recalls the daring Carthaginian leader who had already crossed the Alps and who is said to have crossed the ridge here to descend to Etruria in 217 BC. Not far from the Hannibal Pass, between Mount Maiori and Mount Gomito, was the Serra Bassa Pass. Among woods, clearings and stones, a path connected Rivoreta, on the Tuscan side, with Fiumalbo in the Modena area.

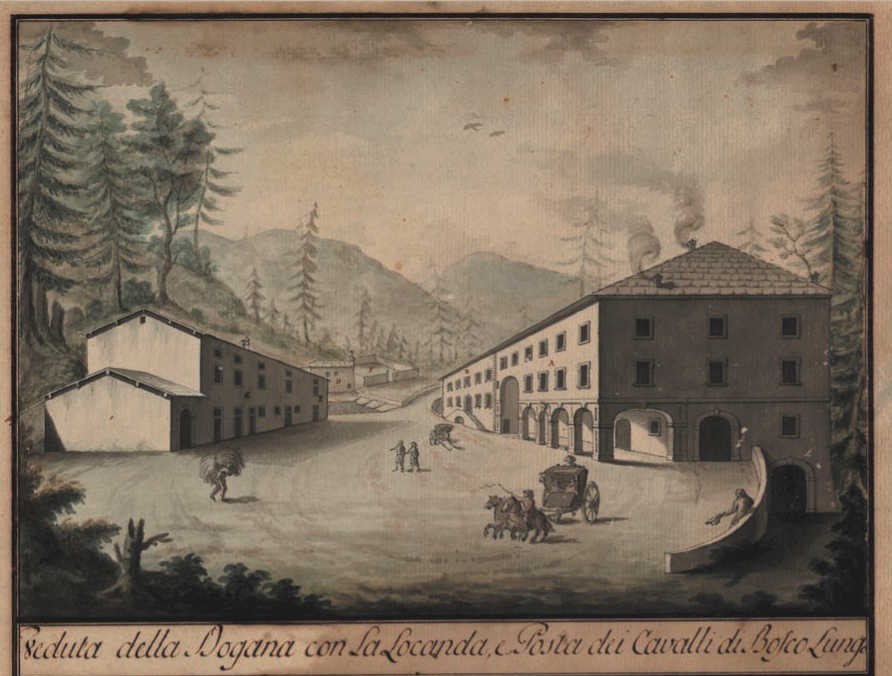

In 1781, at the behest of the Grand Duke of Tuscany, Leopold of Lorraine, and the Duke of Modena, Francesco d’Este, both of Habsburg descent, the Giardini-Ximenes road was inaugurated, named after the two designers. It was a work of art for the time, which quickly became much more popular than the previous roads. The work led to the opening of the Abetone pass, where the workers found a majestic fir tree on the route.

It took three days of constant axe strokes to cut it down: from then on, the place was no longer called Serra Bassa, but Abetone. The first nucleus of the future town was built close to the pass, and from its birth it was divided in two by the state border that crossed it, a border marked by two pyramids that still exist today. Postal stations were then built to serve the road, including Boscolungo, where the new Tuscan customs house was located. Equipped with inns and stables for the horses, the posts soon became centres around which grew settlements, now beautiful towns, “daughters of the road”. The road then continued north to the Brenner Pass and from there to Vienna, the capital of the Habsburg Empire, all within the sphere of ‘friendly’ territories. Even today, this road (with the names SS12 and A22) is the busiest route to and from Europe.

One of the first excellent users of this route was Vittorio Alfieri who wrote in his autobiography: ‘Here I am, therefore, on my way. By my usual direct and very poetic road from Pistoia to Modena, I go very quickly to Mantua, Trento, Innsbruck…’. It was 1784.

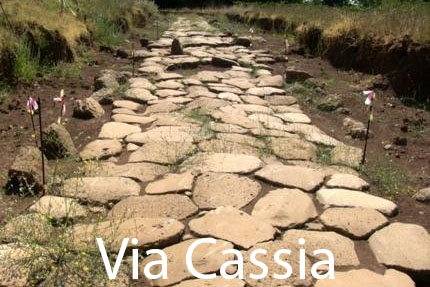

Via Cassia – from Pistoia to Arezzo

After the Romans had colonised the Etruscan peoples of Etruria and began their penetration northwards, they needed to rely on easy and quick routes to fight the Ligurians and Celts in order to easily reach the war zones with their armies.

They began to build consular roads that had specific characteristics: they had to be as short as possible, straight and easy to pass, and therefore plains and the easiest passes over hills were sought. The width of the seat had to allow the exchange of two chariots.

Around the middle of the 2nd century BC. B.C., the construction of a road was initiated to allow an easier and faster connection to the regions north of Rome. This was not to connect Florence, which was not yet a colony, but to enable the army to reach the war zones, as well as an obvious need for an administrative connection to the newly occupied territories. What was the route chosen? As far as Arezzo, everyone is convinced that the road largely traced the route of the previous Etruscan road system.

After Arezzo, it is thought that the road, built ex novo with the characteristics of a military road, found favourable ground on the left bank of the Arno, without crossing the river. It was not, therefore, the road that is now called the Setteponti and that in the Middle Ages was called the Via Sancti Petri, because it was a “connecting” road. The consular road was a “speed” road: the routes could not have been the same. In addition to the tortuous and difficult nature of the ancient route, the torrents that come down from Pratomagno are much more numerous and abundant than those on the opposite slope.

The itinerary we propose, starting from Porta San Lorentino and heading northwards from Arezzo, reaches Ca’ Rossa with a straight stretch of more than seven kilometres, so functional that it has been handed down to us unchanged. Who could have built this road if not a Roman consul?

In 123 A.D., Emperor Hadrian ordered the reconstruction of the Cassia, which, more than two and a half centuries after its construction, was in a disastrous condition. Near the year 1000, when trade and contacts of all kinds between Florence and Arezzo intensified, the road, called ‘Via Vecchia Aretina’, became the main route to Rome. Many important people travelled along it, as Fr. Giovanni M. Montano writes in his work Motivo Francescano in Piazza San Gallo. In 1211, St. Francis also passed through here, who “took the Valdarno road, stopped at Ganghereto, near Terranova; went down to Castel San Giovanni, stopped at Figline, and then, passing through Incisa, crossed the Incontro hills and descended into the Pian di Ripoli, arriving in Florence by night“.

Montaigne gave a famous summary of his trip, praising, among other things, the hospitality of the Osteria di Levane.

Lorenzo Bigi